Though it’s easy to get the impression these days that virtually everyone has gone back to embracing the joys of canning and preserving, in truth the reality is that very few North Americans ever purchase produce of any kind, let alone go through the trouble of canning. There are those that are tempted, though. They’ve read the articles, seen the television programs, listened to the podcasts, bought the cookbooks, and are very much inclined to can and preserve. One of the things that can hold a lot of potential canners back, however, has to do with quantity. Most recipes for canning and preserving are high-quantity. They’re geared toward stocking a pantry for a long winter, or for the apocalypse—whichever comes first.

Small-batch preserve recipes are what most novice canners need, though. They want to give it a shot, but they’re looking for something that’s not a huge undertaking. Something that doesn’t require a large capital investment. Something that pays dividends.

We discovered the pleasures of small-batch canning years ago, back around the time that we first started experimenting with touristic preserving, or small-batch canning as DIY souvenirs. We didn’t rely on a single set of instructions at the time. We just based our experiments on what we already knew about canning. After all, Michelle was already a pretty expert canner, and had been for some time. But we’ve always been struck by how little encouragement there is to can in small batches.

Recently, though, we discovered a particularly sublime small-batch jelly recipe, in Nigel Slater’s Tender, vol. 2. This shouldn’t have been a surprise. Slater is exactly the kind of food writer who you’d expect to have written such a treatise, given his devotion to fruits and vegetables and his fine-tuned attention to seasonality and to the pleasures of the garden. He’s also someone who never expected to become a serious canner, which may partially explain his openness to all different approaches to preserving. “I find it slightly amusing that I am now the sort of person who makes jellies and jams,” he writes. “The process is relaxing and somehow good for my wellbeing. Twenty years ago I would have laughed at the idea of ever pouring cottage garden fruit through a jelly bag, let alone labelling my own jars of jam. Getting older isn’t all bad.”*

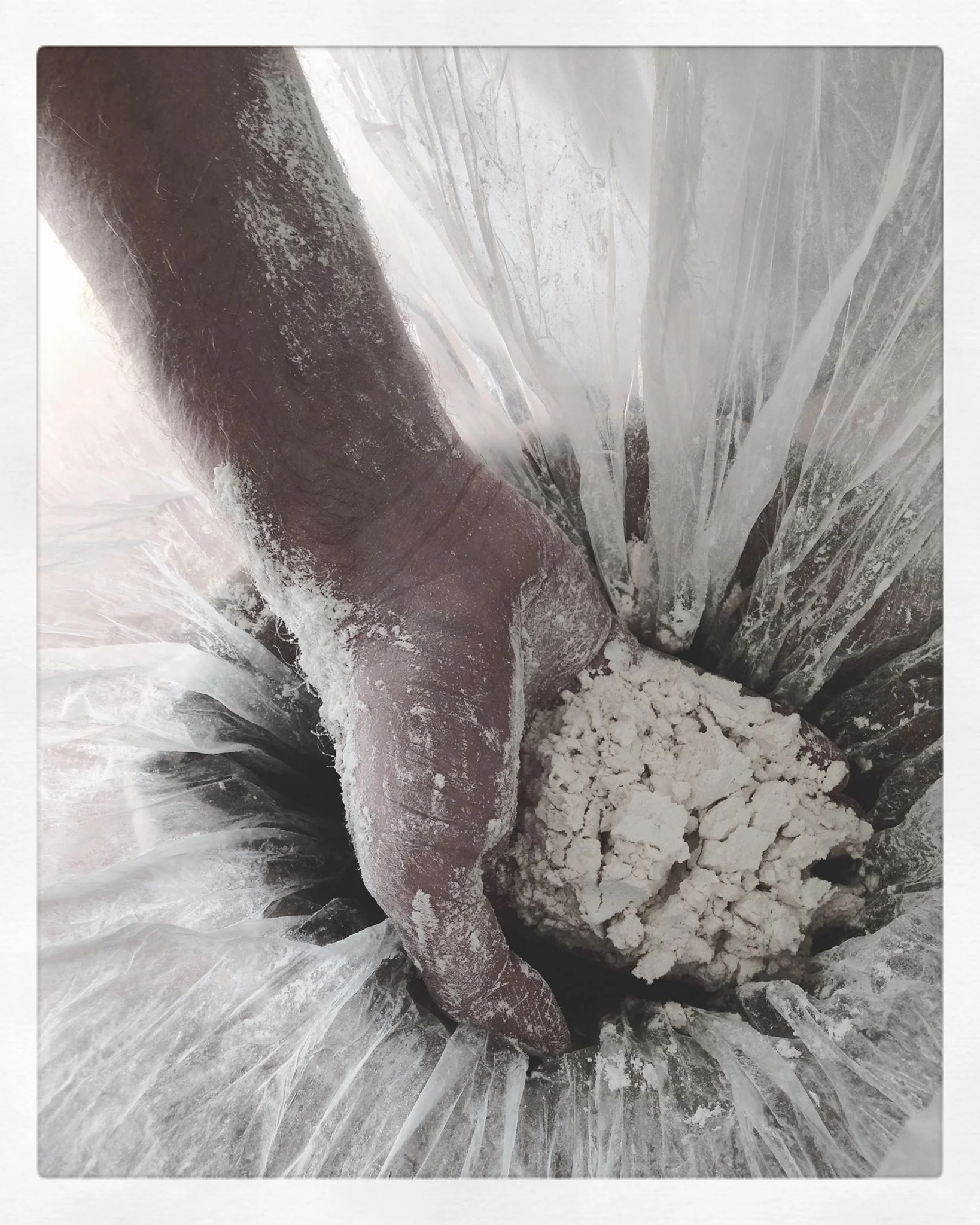

fig. a: high summer berries

Michelle had picked a beautiful mix of berries from our garden—redcurrants, raspberries, and blueberries—and was looking for inspiration. When she came across Slater’s recipe it struck her as especially well-suited for her needs, even if it was rather unconventional: he recommended virtually no liquid, and his cooking time was very, very short. But most importantly, Slater brought his berry mixture to gel stage before passing it through his jelly bag. She had her doubts, but she decided to follow the instructions closely, and Slater’s recipe ended up putting her apprehensions to shame. The results were truly exceptional: the finest, loveliest jelly she’d made in quite a while, and one that required a minimum of effort.

fig. b: still life with quivering jelly

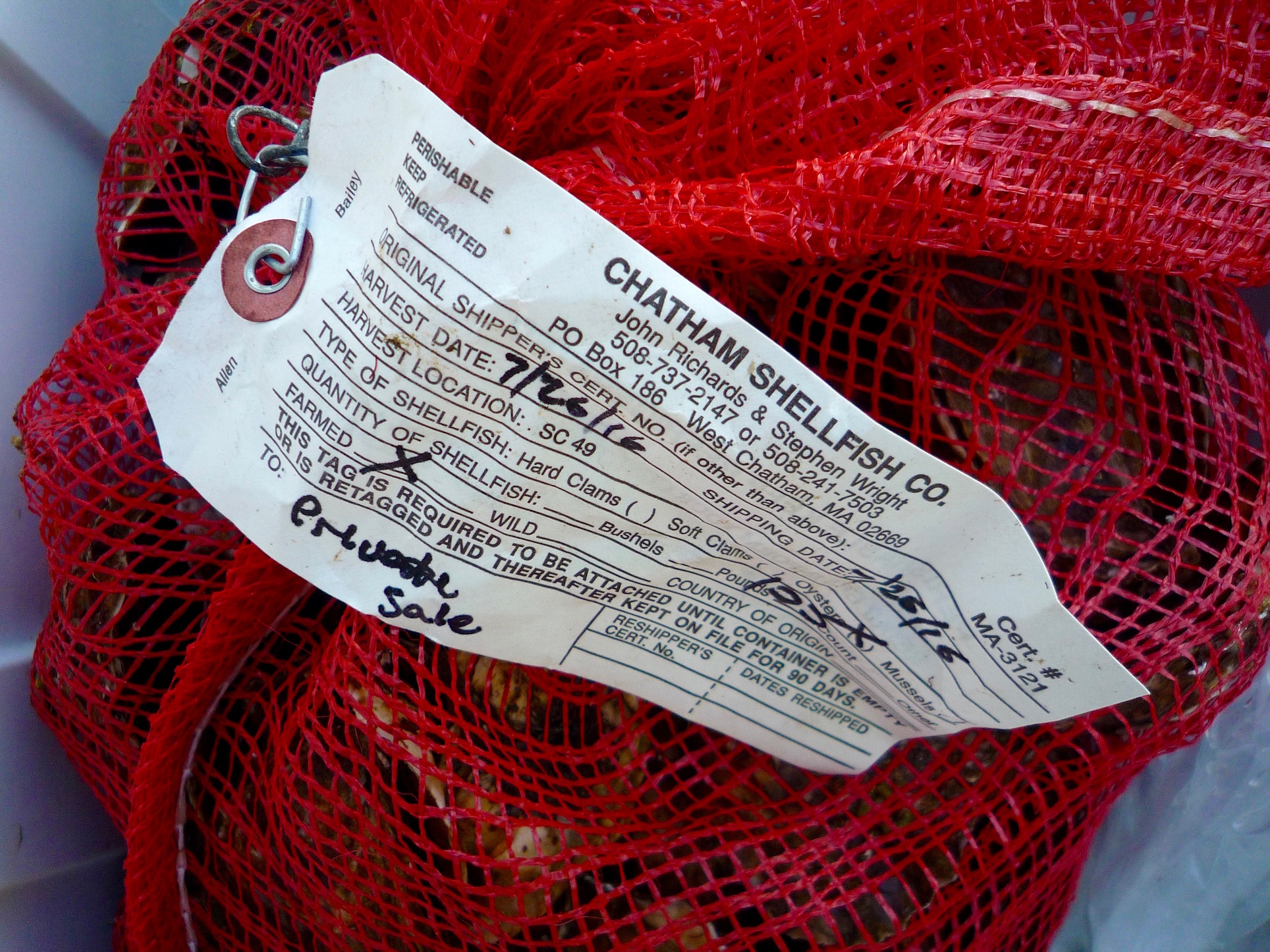

It did require a tiny bit of equipment, however: a nice, deep stainless steel pan to cook the fruit in, a jelly bag, and some jars.

fig. c: Nigel’s jelly bag

But with its simple method, the small amount of fruit it requires, and its easily adaptable equal-parts-fruit-and-sugar formula, this is a recipe that makes preserving high summer berries as easy and as satisfying as possible. See a beautiful bunch of berries at the farmers’ market? Pick them up. Have some in your garden? Gather a few handfuls. Know some friends who happen to have a bumper crop? Unburden them.

Here are the essentials of Slater’s recipe, including its wonderful, somewhat poetic, but very appropriate title:

A Quivering Jelly

450 g redcurrants

A small handful of blackcurrants

450 g white sugar

Put the berries, still clinging to their stalks, into your nice, deep stainless steel pan. Pour in the tiniest amount of water, barely enough to cover the bottom of the pot, then add the sugar. Place on the stove over medium to medium-high heat, depending on the strength of your flame/element. Gently bring to a boil, stirring from time to time, and boil for eight minutes, and eight minutes only—“no longer or the flavour will spoil,” according to Slater. Pour the mixture through a jelly bag set over a wide jug or bowl. Let it be until all the juice has dripped through. Resist the urge to press the fruit in order to produce more juice. Doing so “will cloud the jelly,” Slater points out, spoiling its breathtaking translucency.

Pour into clean jars you have sterilized with boiling water from the kettle and dried, preferably in the oven. Can using sterilized lids, or follow Slater’s instructions by cutting discs of greaseproof paper to fit over the preserve, then covering tightly with a screw-top lid, before storing the jars “in a cool, dry place.”

Of course one of the major advantages of small-batch preserving is that you don’t really have to go through the trouble of canning at all. Put it in any kind of clean container you like. Keep it the fridge. Eat it now. Enjoy it in the moment.

This jelly is so utterly perfect, it won’t last long.

aj

*Ain’t that the truth?